Note On 'K'

Discourse on K-pop's title risk losing its identity for the sake of rebranding

Thanks for reading this edition of Notes on K-pop. Your free subscription helps inspire my work and fuels me to pursue original essays and interviews like these. If you’re already subscribed and able to, I hope you’ll consider upgrading to a paid subscription so I can keep this newsletter going, plus you’ll get access to unique for-pay-only content. Thank you for reading, and all your support!

As we rapidly race towards the end of 2024, it feels like there’s a lot of talk lately about what exactly is “K-pop” and how that “K-” is impacting it.

In the past few weeks, I’ve seen op-eds, interviews, and conversations among fans across social media about whether the “K” is holding back Korean popular music. These discussions have been happening for ages, but the recent uptick largely surround three instances: no Korean acts being nominated for the 2024 Grammy Awards, the BBMAs’ K-pop category, and reports of Bang Si-hyuk talking about the future of Korean music, or just Hybe’s music, needing to disassociate from the “K.”

Beyond that, there’s a focus on K-pop-influenced groups in the west, with Hybe and Geffen’s KATSEYE and JYP Entertainment and Republic Records’ VCHA soon to be joined by SM Entertainment planning to form a UK boy band in collaboration with production company Moon&Back. Along with the rise of XG, a K-pop-style girl group from Japan who declare themselves “X-Pop,” there is, of course, lots of capital “D” Discourse.

You’re probably assuming that since I write a newsletter called Notes on K-pop, I have strong opinions about this all. But to be honest, I’m too much of a Libra for that, and my thoughts aren’t actually all that important at the end of the day.

I have enough thoughts as an outsider covering K-pop for about a decade now about what K-pop means or doesn’t, and have written about the ideas of what K-pop is or isn’t several times. Even for this newsletter I’ve addressed it a few times, and I’m sure I’ll continue attempting to do so as long as I’m writing.

I think a lot of what’s going on is coming down to the idea that from a branding perspective when operating in the Americentric world of global enterteainment, it’s tempting to promote dropping the “K” of K-pop. Racism, othering, and western prioritizing are still true barriers to what K-pop acts face. A few people in this r/K-pop thread had really good oppositional perspectives, some pointing out these things and others pointing out that, on the flip, Korean artists shouldn’t need to make themselves smaller in any way to fit these western-fulled globalization efforts, so I hope you read and engage in the convo there if you think it’s of interest.

One thing that I feel like I want to talk about is that I think a lot of people are also missing the history of it all: K-pop has always not been just “K-pop.” The term “K-pop” is relatively new, and it doesn’t really matter all that much at the end of the day how it’s applied, at least not to me personally: I’ve had countless friends - especially those who grew up in Asia - tell me they thought BoA, one of the pioneering K-pop soloists, was an anime-OST-singing J-pop star. Obviously, this was an intentional marketing tactic, but it worked.

I distinctly remember when I first became a fan back as a teen that I’d never really hear any idols or any other Korean entertainer on variety shows mention the term “K-pop,” except maybe on English-language Korean network Arirang. “K-pop” is not a Korean idea: it’s one applied to the multitudes of Korea’s music industry by those looking to generalize the industry beyond its own national borders, primarily meaning idol music but broadly applied. Over the years, it came to represent the popular music scene operating in the Korean music industry when used generally. But 9 times out of 10 if I talk to a Korean source or industry insider, saying “K-pop” and “idol music” is interchangeable; the term is a brand marker, at the end of the day, and rebranding happens all the time.

So, no. I don’t really think the term matters as much as others do. Language changes, and categories of music in general are typically fluid. But I do like the term, as obviously I have quite an affinity of it.

For me, the biggest takeaway of a lot of these conversations is not necessarily the importance of terminology or branding, because those at the end of the day do not really define K-pop: that’s the industry, the artists, and the artistry.

As vague as the term is, there is certainly a artistic style to K-pop, which makes it very practical to want to maintain this branded identity. But I’d argue, as are others, that in recent years, K-pop artists have to some degree lost that: the identity of K-pop that made it blow up in the western artistic memory is the adventurous, experimental, avant-garde-ness. There’s still that, but I think most longtime, or even newer, K-pop watchers would admit the music and industry has leaned less towards creative explosions in recent years and instead shifted to trend-chasing.

Lately it feels like anytime an act does something super refreshing, it feels invigorating… and then everyone attempts the same thing, and it feels pretty tired really quickly. That’s not to say there isn’t good music and artistry coming from the world of K-pop nowadays, but that sort of experimentalism is no longer necessarily as much of a distinctly K-pop aspect as it maybe used to be.

This may be a listener base change sort of thing, and that’s fine, but it also has changed the identity. Complaints about noise music abound, and I saw a YouTube comment the other day that was so hilariously sad to me that I had to screenshot: “This song is so easy to listen to, it’s just a reallly good pop song. no silly nonsensical dance breaks, no screaming or chanting or belting, no weird raps. we need more GOOD music like this!” the user wrote.

While I’ve definitely been of the “this is an absolutely ridiculous moment for a rap” and “WHY DO WE NEED A DANCEBREAK HERE” mindset at times, because it is an absolutely wonderful to have a reallly good pop song at times as this user says. But K-pop has always been pushing the limits of apparent creativity and produced wonderful art because of that. I don’t think every song needs to be quirky, creative, or mind-blowing, but when a lot of those facets are what made K-pop so special in the first place to grow to the heights it’s currently seeing, it feels like maybe we as an audience and industry need to reassess what the values are.

The quality is still there but there’s been a sort of flattening of it all. I recently have been working on my end-of-year lists and been surprised by how many songs I’ve enjoyed. (Less so on the album front, since true albums seem to rapidly becoming a thing of the past, but that’s for another newsletter!)

All of this is to say that calling it K-pop or defining K-pop as one thing or another doesn’t really matter to me at the end of 2023 as much as what it is does. If the multitude of facets that define K-pop are limited to its title and trying to rid itself of that title means to change it to fit other values, then a battle of its identity has already been lost.

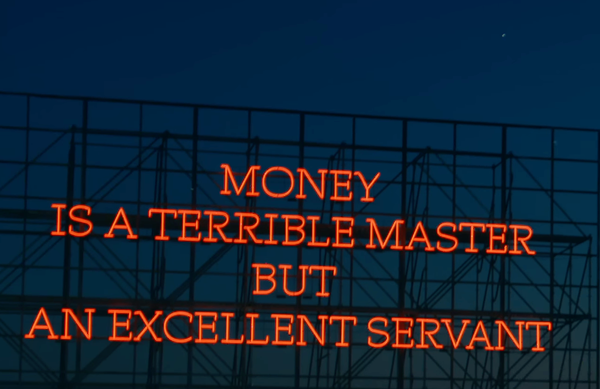

At the end of the day, I don’t think calling something by another name is really going to rid it of its identity. Ridding it of its identity, however, is something that I think we should all be very cautious about. And, of course, rebranding doesn’t necessarily always go well for the bottom line, which seems to be where a lot of the consternation is coming from despite things going fine for some (but not all) of the biggest K-pop companies, so I for one am very curious to see if it’s possible for K-pop to exist by another name.

What I’m working on

Ahead of the finale that formed the upcoming Hybe x Geffen girl group KATSEYE, I spoke with the 10 finalists of The Debut: Dream Academy for Nylon.

For Yahoo Entertainment, I spoke with Philiana Ng about the state of K-pop in 2023 for girl groups.

What I’m listening to

It’s end of year season, so I’m trying to kickstart my storage-space-lacking brain and recall all the music I loved this year by going through the 600+ K-pop music videos released this year that someone kindly compiled on YouTube.

I’m also quite honestly in love with Red Velvet’s Chill Kill album. They’re a group that never disappoints with their full-length albums, and although I don’t think this necessarily surpasses the glory of their prior two, it’s nice to hear Red Velvet back in all their glory. Personally, I’m especially captivated by Underwater and Will I Ever See You Again?

In the news

I’m a bit behind on these newsletters, so here’s a quick rundown of articles I’ve been reading.

Kakao’s alleged stock rigging to buy SM now has the founder promising reforms, even amid more indictments.

Former YG Entertainment chief Yang Hyun-suk has been sentenced to suspended jail time after being found guilty of coercing an informant to withdraw a testimony. This comes as YG is at a fork in its future, with BLACKPINK’s contract situation still unclear, recently parting ways with G-Dragon, both of which are major money makers for the company. New girl group Babymonster is, according to some analysts, the company’s last chance to get out of a bad situation, and just days before their debut it’s come out that one potential member, Ahyeon, is not debuting.

Fifty Fifty's sole remaining member Keena is moving forward and will represent the act at the BBMAs tonight after a whirlwind of a year full of major success and lawsuits.

On a lighter note, Live Nation and JYP Entertainment struck a deal for more tours.

What I’m reading

’ “Up Close and Personal” explores some problems with fan service.

’s piece “The big business of stan culture” is a must-read for anyone trying to understand fandoms in the 2020s. “The unlimited spring of emotion does not differentiate between love and hate. The tantrums, the anti-fandom, the harassment and abuse of perceived enemies, whether fellow fans or public figures, is a feature of the doctrine, not a bug.”