K-pop's neverending live performance

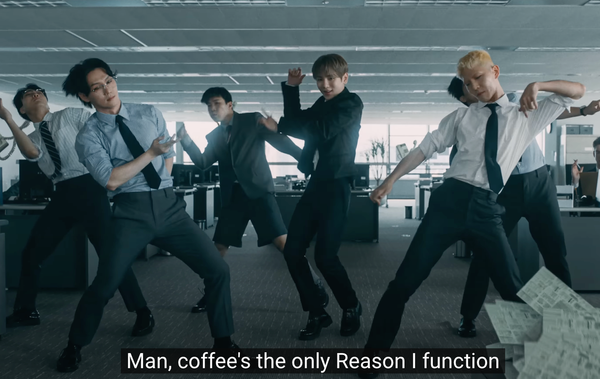

Nowadays, we live in a world where everyone is expected to perform all the time for social media, whether with awareness or unwittingly: you can wake up thinking it'll be a normal day, but by midnight your life can have changed because a video of you on an airplane went viral. But what does this mean for performers themselves, especially K-pop stars who already live a life of heightened performativity?

Over the past few days, a series of incidents have blown up my group chats as friends debate what is or isn't appropriate behavior of and around K-pop stars.

The two biggest situations that are currently buzzing are things you may or not be familiar with: Le Sserafim's Coachella performance, which has received both positive reviews for their high-energy and immense criticism for their shaky vocal performance*, and Stray Kids' privacy, after a merchandise brand, SLBS, they work with allegedly invaded their privacy and also auctioned off items they wore during a fanmeet without consent.

Although they look like very different situations I want to suggest that they're actually wildly different examples of the same thing: celebrities demanded to perform regardless of the limitations of humanity. For Stray Kids, they literally were gone and their proximity was sold. For Le Sserafim, the live experience of a concert was expanded into a livestream. One was an instance of invasive forced post-performance and the other was an instance of planned expanded-performance.

Just a little FYI: I've been thinking a lot about some "big picture" thoughts that I'm still working through and will discuss in this newsletter. This is one of them. Please feel free to comment if you agree, disagree, think I don't know what I'm talking about, or just have something to add, as I'd love to hear insight.

Regarding Le Sserafim, I wasn't there but based on what I've heard it seems the live audience, the one that mattered in earnest for a music festival, typically enjoyed Le Sserafim's. The livestream, an extraneous add-on to modern-day music festivals, however, is where all the problems became apparent.

Similarly, with Stray Kids the incident happened also as a sort of add-on: the group held a fan meet, and SLBS had an auction after the fact, attempting to secretly auction the clothes they had worn as a sort-of bonus event.

In both cases, these idols performed. And then were kept performing even beyond their own human limitations and/or awareness.

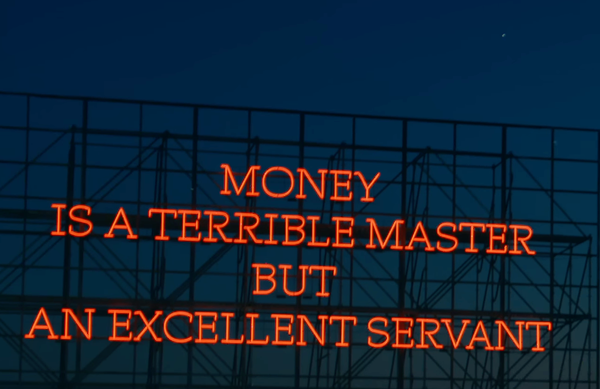

For Stray Kids, they're performing as objects of affection in a fan meet, performing as brand ambassadors, and, unwittingly, performing covert intimacy. SLBS's apology claims that they wanted to give fans a chance to own something so special, and, of course, profit off of that closeness that fans seek to own something special from their faves.

This is a situation built out of one key facet of K-pop idoldom: the parasocial relationship, which relies on deep emotional affected connectivity and/or feelings of ownership.

For Le Sserafim, they're performing as idols in a festival, and performing as hot girl pop stars (it's a genre, I promise you). Coachella sold tickets to a live event, and also hosted a livestream, which are hugely different sorts of audiences. Now, since the performance, Coachella has been a buzzword when in association with Le Sserafim, and I'm sure many people will tune into Le Sserafim's second performance this weekend to see how they do. (I imagine they're all pretty stressed about it so I hope people can have the grace to give them a second chance.)

This is a situation built around another facet of K-pop idoldom: the high standard, which relies on constant perfection across every moment and medium.

So if you're always on, always engaging in a parasocial relationship and always performing at a high-level, whether it's singing or simply living, the lines of what is appropriate behavior from those around you of course must falster: you are an idea, not a person. People can invade your privacy, and criticize to no end. They can love you, they can fight for you. Because when the "you" is a public art display, the performance is living.

The way that statue idols give people a place to focus their religious energy, human idols give people a place to focus their social energy. Engaging with K-pop idols in any way almost always means that in some way there's a connection-based interaction occurring, whether it's from the idol to fans, or the businesses around K-pop towards fans.

We live in an era of complete performative interconnectivity, so it makes sense that that all visible moments of an idol's career can, and perhaps even should, be engaged with in any way that you as a fan, as a consumer, as an observer, can. It's not necessarily a good or bad thing, it simply is, as unfair, as uncomfortable, as unfathomable as it is sometimes.

Regarding SLBS overstepping, fans were pissed. How dare the company, and the fans who went along with it, take advantage of the purchasable proximity to Stray Kids? SKZ have licensed their brand to a degree for the collaboration, and this is not only kind of icky but also presumably a breach of contract. But it's also perhaps more a breach of what is appropriate or not towards idols who are in fact just normal human beings.

Regarding Le Sserafim, it was the members' themselves who were upset by the debate overtaking the importance of their Coachella performance: Sakura wrote a letter defending their performance and Chaewon shared a video of Doja Cat with with her middle finger up, though later deleted it. For them, this is one of the biggest days in their career and they're being horrendously dragged for it. Right or wrong, it's a lot for anyone to be the internet's favorite punching bag of the day. (And especially hypocritical when discussing female K-pop idols. I can't help but wonder how long we'd be having these discussions if this was a male act who came under such fire.)

I personally don't know if neverending performance is really the right way forward for humanity as a whole, and certainly not for individuals. But that's the reality we live in at the moment, and until we as society culturally, capitalistically, change, we're in a world where people who publicly engage are performing not only for a moment in the spotlight but constantly.

What I'm listening to

QWER's Manito album is a perky pop-rock confection that recalls a lot of the vibrance of the early second generation of K-pop, with my brain keying me back into Younha's earliest releases, but also more recently Choi Yena's peppy style. I didn't even realize until after I listened to the album quite a bit that the group is a band: I simply liked how bright and exuberant it was, with a bit of glitchy synths sprinkled in touching on everything that my ears' love. Nick at the Bias List suggested it's reminiscent of Lovelyz, which I definitely see, and there's definitely a classic J-pop influence.

Between QWER and Day6 doing well at the moment, I see a lot of people talking about how pop-rock bands are thriving in Korea. But I'm going to argue something different: people love pop songs, and they're leaning into more traditionally structured ones, especially on Korea's charts. Between this and a few boy bands' recent releases, I think some A&R folks in Korea decided late last year that 2024 was going to see a return to more straightforward song structures versus the more performance-focused norm of recent years. Neither is bad or good, but it does feel like we're seeing more traditionally popular pop hits generating at the moment, rather than simply fuelled by fandom or fame, though of course many of these songs are from popular acts.

What I'm reading

-There's a lot of news about K-pop's stocks at the moment due to recent reports going live, so, of course, CNBC covered some of the news (as CNBC apparently does nowadays). Which means that my first-ever outlet, NBC New York aka WNBC published it. I don't know why my Google Alert showed me the WNBC version instead of CNBC's original report, but it did. And it made me do a lot of thinking about how 10 years ago when I was working at WNBC, even covering KCON New York was out of the realm of interest. Oh how far we have come! I may write about these stock movements still, but in the meantime, feel free to read "K-pop stocks have sold off this year, but Goldman sees a turnaround."

-The Pudding's visual essay about "What Makes An Album the Greatest of All Time?" is a great experiential read.

-Luminate, formerly Nielsen Music, has a weekly newsletter that I enjoy for the data. The "Tuesday Takeaway" from April 9 had some interesting insight that I'm thinking a lot about: "Diving deeper, we find incontrovertible threads of inclusivity and change weaving their way through the fabric of our entertainment landscape. In music, Latin and World Music (including K-Pop and Afrobeats) soared in 2023 as the fastest growing genres in the U.S. Since 2021, we’ve also seen a -3.8 percentage points decrease in English-language music’s share of the top 10K most streamed songs in the country. Simply put, U.S. audiences are engaging with non-English music more than ever before. And it appears this trend is here to stay, as Millennial (57%) and Gen Z listeners (59%) show even greater propensity to listen to artists from other countries."

Also, as always, a big fan of First Floor, even though I am a flop at reviewing, avoid reviewing, and am trying to work myself up to to more reviews because it's an creative skill I wish I was an expert at.